Tamil Tiger warfare via... Rambo: thoughts on the complexity of South Asia

Location: Woodstock, Georgia

Subject: the subcontinent; South Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh)

Reading material: William Dalrymple's The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters (Oakland: Lonely Planet Publication, 2005)

Impetus: Class, History of Modern India and South Asia

The strange thing about getting my book list for this class back in January was that not only did I already know the book, I had bought it in high school off Amazon.com, after reading many positive reviews. Something had tickled me about India, and I was obsessed with the "travel essays" section of bookstores at this time (which, I should add, rarely carry Dalrymple's book). When the material I was grabbing seemed mostly dull, and the enormous Lonely Planet country and traveling guides were mostly just a tease--with their lists of hostels, restaurants, and sites--I turned to the internet, and found The Age of Kali.

The strange thing about getting my book list for this class back in January was that not only did I already know the book, I had bought it in high school off Amazon.com, after reading many positive reviews. Something had tickled me about India, and I was obsessed with the "travel essays" section of bookstores at this time (which, I should add, rarely carry Dalrymple's book). When the material I was grabbing seemed mostly dull, and the enormous Lonely Planet country and traveling guides were mostly just a tease--with their lists of hostels, restaurants, and sites--I turned to the internet, and found The Age of Kali.

Back in 2004-05 though, I don't think I had the background knowledge or the sensitivity to appreciate his collection of essays on various people, customs, and locations across the subcontinent. I was a teenager; one who had enough curiosity to buy the book, but perhaps not yet enough to read through the whole thing. I think I read the first two essays.

So upon seeing this book on the list of requirements alongside six others, I saw this as an unexpected chance to try again, nearly six years later. This time around it's a breezy read, filled with tiny insights and often conundrums that only India could present to the outsider's brain. How do we reconcile the actions of an eighteen-year-old young woman, married for less than a year, who jumps atop the funeral pyre of her deceased husband, therefore martyring herself in the classical Brahman practice sati? One such case embroiled all of India in a highly publicized legal debate from 1987, when Roop Kanwar walked calmly to her own death, to 1996, when the villagers involved in the funeral were acquitted. Was it devotion to her husband and to her religion that led her willingly to death by fire, or, in the easiest to rationalize theory, was she drugged by the villagers and her husband's family (therefore, basically complacent)? Or, as some anonymous village sources told newspapers in the flood of reporting that came from their Rajastani village in the wake of the death, did she actually try to escape the flames, and was pushed back upon them by village men? As there was no evidence, and no witnesses who would argue the latter in court, all involved men were let off in 1996 when the case ended. And rightly so; there is no evidence against them, and though womens' rights groups and western media might find it uproarious, we cannot assume she did not do it of her own accord and imprison men for crimes which they may never have committed. There is no easy answer; on one hand we must consider the alternative life Roop would have had if she did not perform the sati: she would have been condemned to shave her head, don a white sari, and beg for food for the rest of her life. She was only eighteen; that is an equally frightening prospect. The flip side is that she was relatively educated for the rural region where she lived, and she had lived in the city Jaipur for awhile. Dalrymple tells of the many urban Indians who abhor the idea of her decision being anything other than forced, for, what educated woman willingly does such a thing? (We must keep in mind that sati is an exceedingly rare practice, and in the several dozen of cases since 1947, occurs in rural India.) The point is, Roop could have been at once a devout wife, a scared widow, an educated and religious young woman, and a little bit on-edge--as most teenagers are. The combination may just have produced the event that occurred on September 4, 1987. There is neither easy answer, nor simple resolution. When Dalrymple visits the Roop's village, nearly all the people he talks to claim they weren't even there on the day of the sati.

So upon seeing this book on the list of requirements alongside six others, I saw this as an unexpected chance to try again, nearly six years later. This time around it's a breezy read, filled with tiny insights and often conundrums that only India could present to the outsider's brain. How do we reconcile the actions of an eighteen-year-old young woman, married for less than a year, who jumps atop the funeral pyre of her deceased husband, therefore martyring herself in the classical Brahman practice sati? One such case embroiled all of India in a highly publicized legal debate from 1987, when Roop Kanwar walked calmly to her own death, to 1996, when the villagers involved in the funeral were acquitted. Was it devotion to her husband and to her religion that led her willingly to death by fire, or, in the easiest to rationalize theory, was she drugged by the villagers and her husband's family (therefore, basically complacent)? Or, as some anonymous village sources told newspapers in the flood of reporting that came from their Rajastani village in the wake of the death, did she actually try to escape the flames, and was pushed back upon them by village men? As there was no evidence, and no witnesses who would argue the latter in court, all involved men were let off in 1996 when the case ended. And rightly so; there is no evidence against them, and though womens' rights groups and western media might find it uproarious, we cannot assume she did not do it of her own accord and imprison men for crimes which they may never have committed. There is no easy answer; on one hand we must consider the alternative life Roop would have had if she did not perform the sati: she would have been condemned to shave her head, don a white sari, and beg for food for the rest of her life. She was only eighteen; that is an equally frightening prospect. The flip side is that she was relatively educated for the rural region where she lived, and she had lived in the city Jaipur for awhile. Dalrymple tells of the many urban Indians who abhor the idea of her decision being anything other than forced, for, what educated woman willingly does such a thing? (We must keep in mind that sati is an exceedingly rare practice, and in the several dozen of cases since 1947, occurs in rural India.) The point is, Roop could have been at once a devout wife, a scared widow, an educated and religious young woman, and a little bit on-edge--as most teenagers are. The combination may just have produced the event that occurred on September 4, 1987. There is neither easy answer, nor simple resolution. When Dalrymple visits the Roop's village, nearly all the people he talks to claim they weren't even there on the day of the sati.

And this is India through Dalrymple's eyes and made vivid through his stories and reporting. Messy, multi-faceted, in-your-face, with plenty of moral dilemmas thrown at you...

In fact, one of the most intriguing, and possibly disturbing, revelations in Dalrymple's tales is not in India, but in Sri Lanka; and then, specifically, the northern occupied region of Tamil Eelam. In 1990, when he visits, the country remains embroiled in the brutal civil war, between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamil's brutal homegrown army, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The decades-long war ended, as far as we can tell now, in 2009 with a treaty and the vague promise of some sort of federal representation for long-disenfranchised Tamils. The linguistic and nationalistic origins of this war are a fascinating a sad subject, as the Tamils had been the favorite of the colonial British government, learned in English and given opportunities for more education (classic move by colonizing power, favoring the minority). Sri Lanka (Ceylon) enjoyed quite high levels of growth, literacy and education, and wealth in the aftermath of WWII, far greater than their neighbors to the north (India and Pakistan). In 1956, Prime Minister Soloman Bandaranaike would deal his country a blow (hindsight's 20/20) with the Sinhala Only Act, which effectively removed the Tamil and English languages from governmental and all public sector jobs. In a single move, which was carried on by his widow, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, millions of Tamils were out of jobs, and a generation of Tamil youth were disenfranchised. Marginalized by their own government and left with no say in national policy, the LTTE grew out of a natural vacuum of opportunity.

In fact, one of the most intriguing, and possibly disturbing, revelations in Dalrymple's tales is not in India, but in Sri Lanka; and then, specifically, the northern occupied region of Tamil Eelam. In 1990, when he visits, the country remains embroiled in the brutal civil war, between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamil's brutal homegrown army, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The decades-long war ended, as far as we can tell now, in 2009 with a treaty and the vague promise of some sort of federal representation for long-disenfranchised Tamils. The linguistic and nationalistic origins of this war are a fascinating a sad subject, as the Tamils had been the favorite of the colonial British government, learned in English and given opportunities for more education (classic move by colonizing power, favoring the minority). Sri Lanka (Ceylon) enjoyed quite high levels of growth, literacy and education, and wealth in the aftermath of WWII, far greater than their neighbors to the north (India and Pakistan). In 1956, Prime Minister Soloman Bandaranaike would deal his country a blow (hindsight's 20/20) with the Sinhala Only Act, which effectively removed the Tamil and English languages from governmental and all public sector jobs. In a single move, which was carried on by his widow, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, millions of Tamils were out of jobs, and a generation of Tamil youth were disenfranchised. Marginalized by their own government and left with no say in national policy, the LTTE grew out of a natural vacuum of opportunity.

Dalrymple visits the terrorized city of Jaffna, on the northern Sri Lankan coast, which has been caught in the particular violence that raged from 1983-1990. After a particularly humorous bit on the utterly poor conditions of the hotel where he stays (which hasn't seen a non-Tamil in eighteen months), he has the opportunity to talk to some of the gun-toting teenagers who compose the ground forces of the Tamil Tigers.

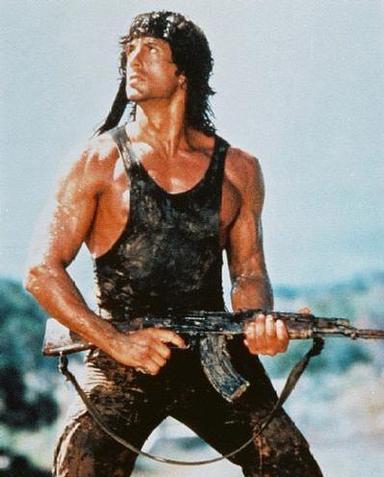

Up til now, we might write all this off as civil war, bloody and ruthless, but not posing any specific moral dilemmas to an outsider. Then Dalrymple meets Castro, a man similarly aged and the mastermind behind some brutal LTTE moves. And then he discovers a very strange source of their warfare inspiration:

I asked him to tell me more about the attack, and he happily compiled. He described the preparations, the spying and the intelligence work. He told me of the long, wet fifty-mile march through the monsoon jungle, the moonlit crossing of the lagoon and the silent belly-crawling as the guerrillas surrounded the camp and cut the wire. As he talked, I was aware of a growing sense of deja-vu. It all sounded a bit familiar, I said. Hadn't I seen a film of this somewhere? He smiled.

'You're right. Our camps are all equipped with televisions and videos. War films are shown three times a week, and are compulsory viewing. We often consult videos like The Predator and Rambo before planning our ambushes. None of us are trained soldiers. We've learned all we know from these films.'

So, I thought: video-guerrillas. To Sri Lanka from Hanoi via Hollywood. It was an arresting idea: real-life freedom fighters earnestly studying Sylvester Stallone and Arnie Schwarzenegger to see how it was done.

Later I saw the camp's video library: complete sets of Rambo, Rocky, and James Bond; all the Schwarzeneggers, including Conan the Barbarian, Conan the Destroyer, and Commando; most of the recent Vietnam films; and, touchingly, no fewer than three copies of The Magnificent Seven. Moralists have often speculated the much of today's violence is inspired by violent movies. If only they knew. Here in Sri Lanka the tactics of an entire civil war--tens of thousands killed, maimed and wounded--seem to be largely inspired by imported videos.

I'm not an advocate for ending violence in movies, and I don't think if that was attempted it would even prove effective in the least; we live in a very violent world. I also do not think that thirty years of the LTTE's military tactics were guided entirely by Hollywood; Dalrymple is just reporting what he's witnessed and making a strong point for his readers. But with the grain of salt, I still find a bit of horror in the idea of Rambo inspiring an actual rebel army of merciless killers. Kids, teenagers, adults in the western world understand the violence in these movies as not only staged, but to some extent, unrealistic. I've never seen a James Bond movie without that over-dramatized, glitzy, glamorous murder--all while wearing a great suit and with accompanying witty dialogue. To my eye it is so clearly imaginary. And so the idea of Tamil Tigers watching with rapt attention and invoking the ideas of battle choreographers is a lesson in my own morality--or at least that of my society's.

I'm not an advocate for ending violence in movies, and I don't think if that was attempted it would even prove effective in the least; we live in a very violent world. I also do not think that thirty years of the LTTE's military tactics were guided entirely by Hollywood; Dalrymple is just reporting what he's witnessed and making a strong point for his readers. But with the grain of salt, I still find a bit of horror in the idea of Rambo inspiring an actual rebel army of merciless killers. Kids, teenagers, adults in the western world understand the violence in these movies as not only staged, but to some extent, unrealistic. I've never seen a James Bond movie without that over-dramatized, glitzy, glamorous murder--all while wearing a great suit and with accompanying witty dialogue. To my eye it is so clearly imaginary. And so the idea of Tamil Tigers watching with rapt attention and invoking the ideas of battle choreographers is a lesson in my own morality--or at least that of my society's.

Part curious, part shocking, this is a real case to consider when we think of the world that exists around us. I've read of plenty of the terrible violence, deaths of innocent people, and refugees who live around the world whose lives have been destroyed or forever changed by this civil war. And it jabs at precisely Dalrymple's point, that we cannot take this region at face value, nor can we easily label it. We cannot lump South Asia's innumerably diverse people into one large group, nor can we simply define what "Indian" means. Most importantly, we cannot transplant our own moral codes atop the functioning of thousands of years of history and define the subcontinent in our own terms; it does not translate that way. The reality is much, much more complex.