Make sure you've had your tetanus shot, and other important things I learned as an archives intern

For six weeks this summer, I worked as an intern in the archives department of the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in downtown Kennesaw, Georgia. When I told people this, they undoubtedly replied, "The museum with The General, right? I went there all the time as a kid!"

For six weeks this summer, I worked as an intern in the archives department of the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in downtown Kennesaw, Georgia. When I told people this, they undoubtedly replied, "The museum with The General, right? I went there all the time as a kid!"

Yes, it is the home of The General, the locomotive that was stolen by the Union in the famed Great Locomotive Chase in 1862, an event that gives the Southern Museum a wonderful spot in the arena of American museums focused on the Civil War. The Southern Museum tells the story of the role of Marietta, Kennesaw, and the Cobb County area, as well as the role of the locomotive, in the Civil War. It is much more today than it was even a decade ago, when it was only the home of The General. Its staff has since made it into a wonderful, ever-expanding museum with several permanent exhibits. In addition to The General and "Railroads: Lifelines of the Civil War," the Southern Museum also houses an exhibit on the history of Glover Machine Works, a local steam engine manufacturer, and the modernization of southern industries like it.

For someone who wanted to learn more about developing effective interpretive programs in museums, it was a wonderful opportunity to work with the staff--many of whom were founding members of its team, as the museum was officially founded as the Southern Museum (and expanded from 4,000 square feet to over 40,000) in 2003.

Over the course of my time there, I cataloged an entire collection from start to finish, including creating a finding aid for it (so researchers can find what they need easily); I helped install a traveling exhibit (the museum is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institute, and the exhibit was one of theirs--"The Working White House"); I helped out at an evening fund-raiser, cocktail party, of sorts; I learned more about the education programs held weekly at the museum; and I did a bit of research on legal issues in the museum world. Throughout, I kept a little list of the truths of the whole world that exists inside the museum.

Things I learned during my internship:

The budget is tight. This is the mantra that all museum business must work within—and around. Do what you can with donated items, such as slightly incorrect—albeit free—file folders for archival materials. In the curatorial department, donations are not always as welcome, as they are oftentimes community members’ old things dropped off at our doors, and are added into the museum’s already stretched storage. The tight budget can often slow or even stop the curatorial and archival goals of a museum, and the mere freezing of a project is in itself a lesson in museum patience. The not processing is part of the experience.

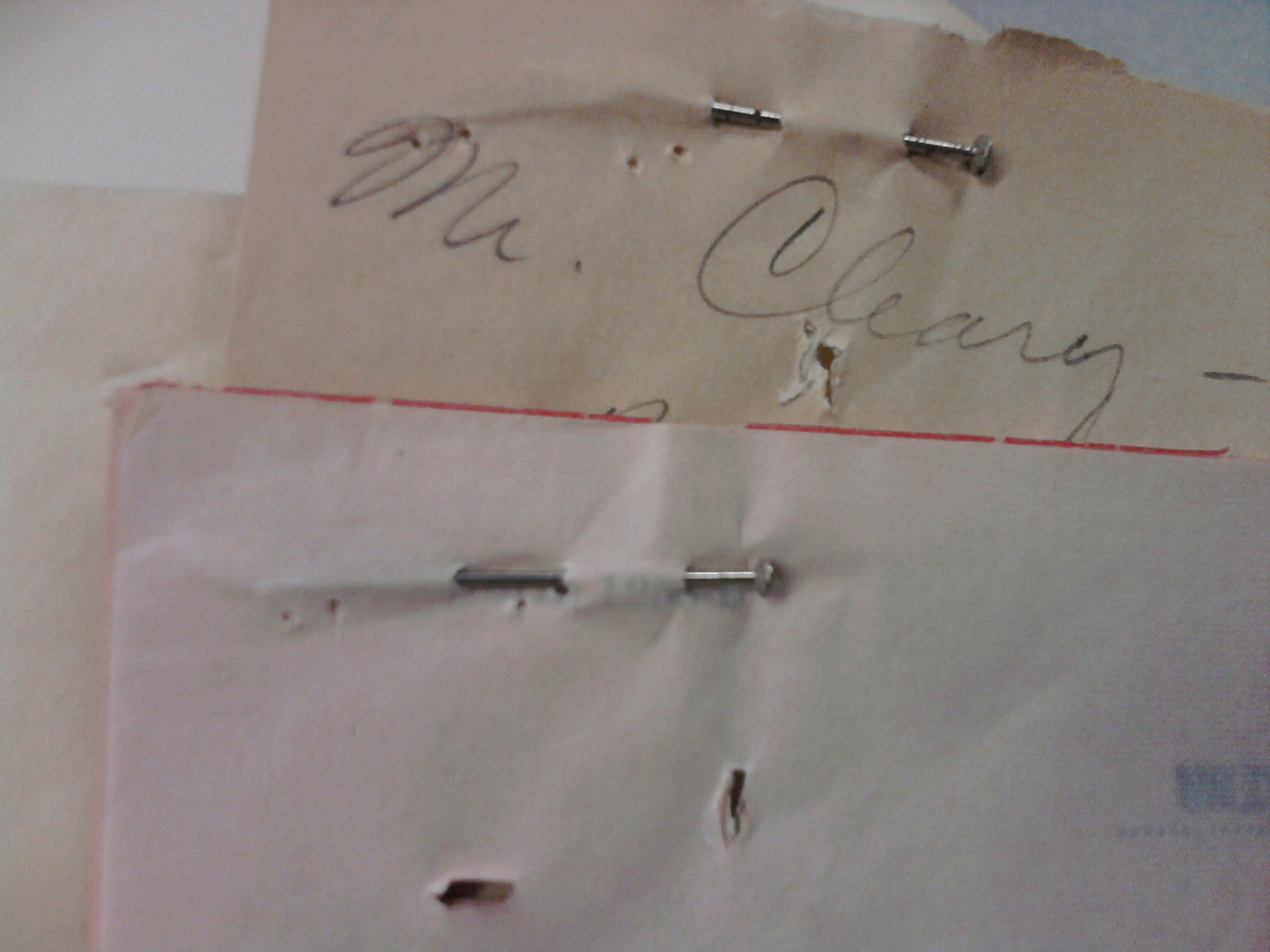

It’s all for the documents and artifacts. This means anything we do must be in an effort to sustain the items we’re working with and keep them as close to their present condition as possible. As Mike the curator told me, our job is to slow their inevitable deterioration. This means removing metals from documents, using pencil only, using acid-free folders, boxes, and tape to hold the materials, and ensuring that our own skin oils and food products do not spoil the items around us. For an intern, it meant pulling out (with an appropriately gentle tool) hundreds of rusty, stubborn staples each day, cursing the use of this office essential while organizing all the staple-free pages into their acid-free folders.

But it’s really all for the community. For, if there is no community for the museum to serve, there is no purpose in its work, no reason to preserve the documents, artifacts, and history it contains. The best way to engage the community is to foster relationships with the children and adults who walk in the door, to keep them coming back; this is done by continually offering new learning experiences in the form of programs and exhibits that expand their knowledge and keep them curious.

And it’s also for your donors. When your museum makes the news and the archivist is interviewed for the radio, it is important that the largest supporters’ projects also get mentioned. Because of news editing, this part was left out at one point during my internship, and we heard about it just a few hours after it was broadcast. When we get press, its important that our patrons are included—rightly so. We also sometimes bend the rules to suit the benefactors’ requests, like allowing them to climb up onto The General, the locomotive that, large as it is, is still an artifact, threatened by its age and the wear and tear of human use. There are simply times when the donors’ satisfaction is paramount.

A man cannot be a museum (however, sometimes he must be). The museum functions only with the contribution and partnership of all of its employees, and the community that arises among them when they come together to complete a project. The director, curator, accountant, volunteer, intern, and janitor are all equally important components of the success and progress of a growing, working museum. After all, with tight budgets, it needs people who are willing to work for free. It also needs people with museum expertise, and people who are good with numbers, and people who care about children. And it requires that they frequently come together and pool their talents. And thus, when working in a very small museum or house museum, the small number of employees must embody many of these skills and be able to perform many of these tasks. The museum world involves wearing many hats.

You must be willing to ask for money. It can be done in very classy or creative ways, absolutely, but the fact remains: the budget is small and the goals are huge. You don’t have to be great with numbers to figure out that equation.

Patience is a virtue. Partly because of the budget, partly because of the red tape involved when doing anything with public money or in a non-profit capacity, things sometimes take longer than planned. Projects wait in the background for years sometimes, waiting for the right grant to complete them, or else for the museum itself to come up with the money. When dealing with third parties, perhaps for outside consultant work, projects are no longer only in the hands of the museum staff, and sometimes you must take a breath, and wait.

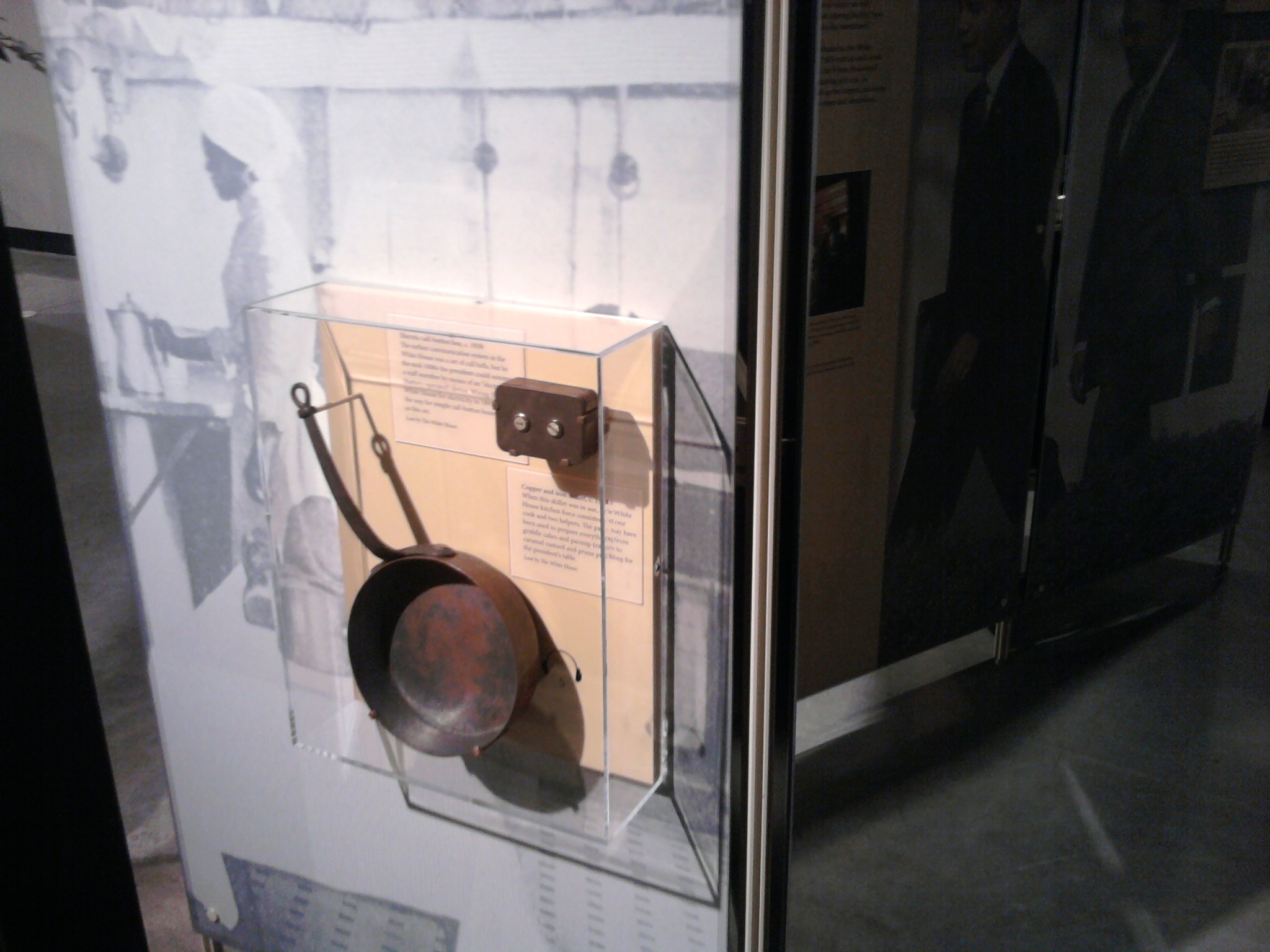

Exhibit set-up is mostly planned chaos. While I was at the Southern Museum, we received a traveling exhibit that belonged to the Smithsonian, titled "The Working White House." The installation of it was a whirlwind of unloading, floor planning, conditions reporting (where you record the nicks and scratches of any of the items you've received so that the museum who owns the items can track the wear and tear of their artifacts and display cases), and actual construction of the hardware that holds up the panels and artifacts. I never even considered the importance of lighting in creating an effective exhibit experience, but it makes all the difference. We walked through the whole thing, panel by panel, with the curator wheeling around on a giant ladder to focus the spotlights at precisely the right angle for maximum ambiance and effect. I also learned a lot about properly cleaning Plexiglas and how to avoid artifact theft (hint, no two screws have the same bit).

Always use a pencil. After recording and numbering an entire collection of boxes, someone might be out in storage and discover another box of random documents that belong with my collection. So, I dig in, I organize them by date, and then place each file into its chronological spot among the rest, thereby renumbering every single document that falls after the new entry (or entries). The folders we use to hold and store each file cost about $1 each, and considering the other axioms of museum life, on budget and limited resources, you can assume that use of a pencil is highly endorsed by all parties. But don’t use the eraser on top that #2—it’s not acid free. Use one of those nice, pink stand-alones.

Always use a pencil. After recording and numbering an entire collection of boxes, someone might be out in storage and discover another box of random documents that belong with my collection. So, I dig in, I organize them by date, and then place each file into its chronological spot among the rest, thereby renumbering every single document that falls after the new entry (or entries). The folders we use to hold and store each file cost about $1 each, and considering the other axioms of museum life, on budget and limited resources, you can assume that use of a pencil is highly endorsed by all parties. But don’t use the eraser on top that #2—it’s not acid free. Use one of those nice, pink stand-alones.

Your work is never done. I finished cataloging an entire collection, from removing the staples all the way down to writing its entire finding aid (i.e. descriptions, so it’s easy for people who want to use this collection for research to find what they want quickly), on my last day at the Southern Museum. Unless, that is, you count the extra box of documents someone found in storage, which had been separated from the others. We found this so late, and it involved so much backtracking (as I hinted at before, with the renumbering and the reprinting of all the box labels), that we decided to keep the collection, as it was then, complete and finished for now. I had tackled a project that some of the other volunteers would not touch, due to its dull nature (the accounting files for various southern railroad companies when they chose to retire anything in its ownership, from tracks to work vehicles to store houses), and since I had so nearly completed it, we left it at that. The finding aid is posted on the museum’s website for anyone who wishes to do research in this collection. But the fact of the matter is, there is still one more box of documents to add it to it, someday.

The museum is a big, kooky family. My boss, the director of archives, is a motorcycle enthusiast who also collects historical guns and sometimes uses them for demonstrations. She used to be a nurse. One of the interpreters does Civil War reenactments and works with cattle-riders and other novelty odd-job folk in Wisconsin; he’s also appeared as an extra in several Robert Redford films. Everyone on the staff was enthusiastic, even, most notably, when dealing with the parts of their jobs that were not always as much fun. The whole staff I worked with was full of creativity, ingenuity, laughter, and kindness, and certainly an array of quirks. I hope their attitudes and teamwork are a sampling of the kind of people who work in the museum world not for its lucrative benefits (joke, there), but for the personal satisfaction it awards them, and for the effects of their work in the larger community--both that of Cobb County and of comparable museums.