Taryn Simon, exploring bloodlines and stories that bind us, through photos

In the middle of a Saturday afternoon, in midtown Manhattan, we were near collapse after a morning exploring the Upper West Side and Central Park, then shopping around midtown. Then we went to the Modern Museum of Art. I felt it essential to visit at least one of the major, internationally-renowned museums New York City has to offer, even while we were resisting the traditional tourist visit to the City.

Taryn Simon, artist and photographer, has a knack for amazing titles. Her current show: A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, I-XVIII. At some point as we neared delirium, we wandered into the photography section of the museum, tucked on one of the expansive floors, and found Taryn Simon's stunning exhibition of photographs. To be honest, the named intrigued me first, as names and titles nearly always do. A great name is the fastest way to get me interested. (I read Angela's Ashes in sixth grade--I know, right?--because I desperately wanted to know who Angela was, and what was her relation to the little grungy boy on the cover; no other reason.)

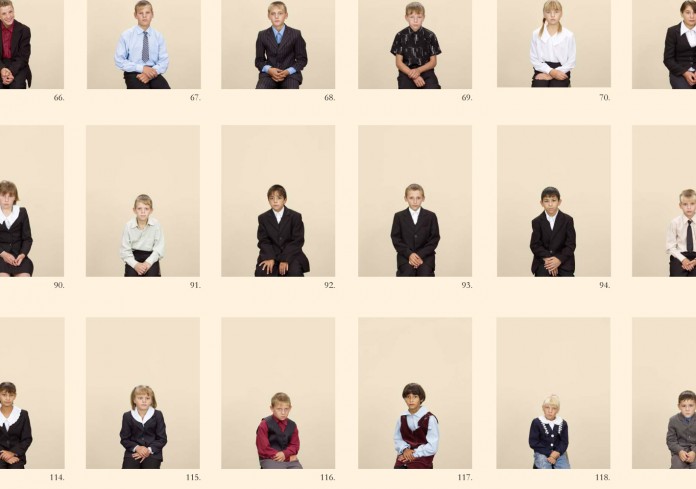

We found ourselves surrounded by austere faces, portraits of men, women, rabbits, sitting each by themselves, amid a series of people (and sometimes things) who are somehow related, whose lives and stories intersect by some grand or small event. There was something about "bloodlines," as after looking deeper at the panels and photographs, I was confused about the organization of the show and its larger meaning. I left intrigued deeply, wanting to spend more time pondering this series, these "chapters," later, but not wanting to buy the $125 exhibition book--which was the show in its entirety, amazing.

Hours later, I am in the hotel room taking a much-needed rest, and flipping through a Time magazine I'd brought with, when there is this bold headline: "There Will Be Bloodlines: Taryn Simon untangles the ties that bind."

I kid you not, I got goosebumps. If I had looked at this magazine a day earlier, I might have overlooked this name, skimmed the article at best. Here was this woman, and her explanation of this newest project, which was four years in the making, and took her to twenty-five countries.

Now I have a proper explanation of the project's theme and meaning:

The organizing principle for this project is what she calls bloodlines: all the living descendants, plus any living forebears, of a single man or woman who sets a story in motion.

And the reasoning, the messy ties and stories and variable havoc that occurs within these "bloodlines" is where her project becomes truly fascinating. It echoes what I see and know deeply: that family lines, genetics, and genealogy have little to do with the way our lives turn out, have almost nothing to do with the events that shape our individual lives in the present.A simple concept, really; and this explains why the tribal man with ten wives, dozens of children, and many dozen grandchildren appears in a massive sequence. And also, why there is a man missing from his own story--a blank canvas appears instead; he was executed for war crimes after the end of WWII and Nazi Germany, but descendants appear after his spot, along with more missing people, via their empty canvases, as well as pieces of clothing that act in lieu of a person, who preferred not to share his or her face in association with this man. Meaning becomes clear.

Simone depicts bloodlines as flowing charts of small portraits--like a living periodic table of the elements. What resonates is the persistence, and finally the insufficiency, of ancestry and kinship as systems for making sense of unruly destinies. To show that blood lineage can be an extremely loopy line, she sought out unlikely subjects; one is a Lebanese man who claims to be reincarnated, so he pops up more than once in his own family history. "I was always looking for a surreal twist," she says, "something that would lead to a collapse of logic."

All the same, even the most outlandish chapters have their universal element. As Simon put it, "We're all the living dead, pieces of what came before." What she means is that we all carry the DNA of our forebears; there ghostly current pulses through us. The intricate machinery of her project is designed to show that blood ties are a weak line of defense against the blows administered by history, politics, or sheer unlucky circumstances. [italics my own.]

Yes. This entire work is more stunningly magnificent than I ever could have imagined, aligning greatly with my own theories on this whole world and what happens to us during our time here.