2011 [a year like no other] and its place in history

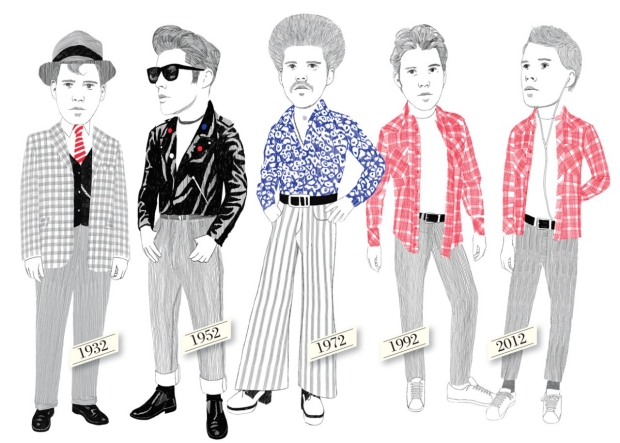

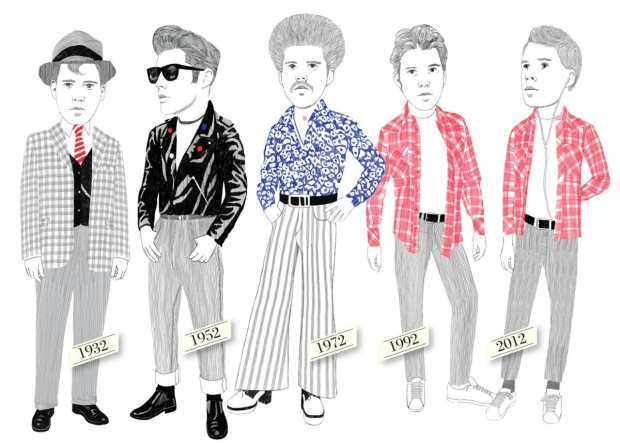

I have read two articles in the last week whose arguments have begun with Francis Fukuyama's 1989 essay The End of History, which argued that as we reached the final demise of the U.S.S.R., "liberal democracy had triumphed and become the undisputed evolutionary end point toward which every national system was inexorably moving: fundamental political ferment was over and done. Maybe yes, maybe no," Vanity Fair's January 2012 issue reports. In this first piece, "You Say You Want a Devolution," the main crux is that in the last twenty years, we have remained in a stagnant state of cultural development. "In the arts and entertainment and style realms, this bizarre Groundhog Day stasis of the last 20 years or so feels like an end of cultural history." Kurt Andersen points to our nostalgic gaze towards the past, and the way our architecture and automobiles have remained looking mostly the same since 1991. We also dress nearly the same. Hip-hop, the last genuinely new form of music, makes an unapologetic use of old music through sampling. Fine art, which recognizably depicted people for every century before the 20th, is back to respectably representing human forms again. "It's the rare 'new' cultural artifact that dosen't seem a lot like a cover version of something we've seen or heard before. Which means the very idea of datedness has lost the power it possessed during most of our lifetimes," he writes. "In our Ben There Done That Mashup Age, nothing is obsolete, and nothing is really new; it's all good." There are two major reasons, he argues, for this stagnated cultural state:

Why is this happening? In some large measure, I think it's an unconscious collective reaction to all the profound nonstop newness we're experiencing on the tech and geopolitical and economic fronts. People have a limited capacity to embrace flux and strangeness and dissatisfaction, and right now we're maxed out.

...The other part of the explanation is economic: like any lucrative capitalist sector, our massively scaled-up new style industry naturally seeks stability and predictability. Rapid and radical shifts in taste make it more expensive to do and can even threaten the existence of an enterprise. One reason automobile styling has changed so little these last two decades is because the industry has been struggling to survive, which made the perpetual big annual styling changes of the Golden Age a reducible business expense. Today, Starbucks doesn't want to renovate its thousands of stores every few years. It blue jeans become unfashionable tomorrow, Old Navy would be in trouble. And so on. Capitalism may depend on perpetual creative destruction, but the last thing wants is their business to be the one creatively destroyed. Now that multi-billion-dollar enterprises have become style businesses and style businesses have become multi-billion-dollar enterprises, a massive damper has been placed on the general impetus for innovation and change.

He goes on to ponder what this cultural moment--frozen mostly for the last 20 years--means for western civilizations as a whole, for their existence and sustainability in the future. I am not convinced it spells anything like the end for the West. But, he has a compelling overall theory, and when you consider the photographs and comparisons through the years of our cultural changes--buildings, clothing, cars--you see he is absolutely spot-on.

I ear-marked the article and set the magazine in my current pile, and excitedly picked up Time magazine's Person of the Year issue, which features, for 2011, The Protestor as the Person of the Year. Absolutely the right call--that's the only "Person" we could choose to represent this amazing, tumultuous year.

And wouldn't you know, the lead article begins its discussion, its explanation of this 2011, with the exact same Fukuyama theory, explained in The End of History, this "end" theoretically beginning around 1990. Then, only as I went to write about both of these articles and t he impact they've had on me as I reflect back over this year and its events, did I realize both are written by the same man, Kurt Andersen. Of course, that explains the similar thought process, and the similar sources of influence as Andersen himself was reflecting back over the year 2011.

The Time article has a more optimistic overture, even while explaining that there is no saying where the future will lead, after this year of tumult and protesting, and voices exploding over the things wrong with the world, all over the world. He points out several things that never occurred to me, things that make 2011 distinct from any other year in the last twenty, since the theoretical "end of history," and that make it distinct from any other year since 1968, and--he argues--even farther back in history.

Once upon a time, when major news events were chronicled strcitly by professionals and printed on paper or transmitted through the air by the few for the masses, protestors were prime makers of history. Back then, when citizen multitudes took to the streets without weapons to declare themselves opposed, it was the very definition of news.--vivid, important, often consequential. In the 1960s in America, they marched for civil rights and against the Vietnam War; in the '70s, they rose up in Iran and Portugal; in the '80s, they spoke out against nuclear weapons in the U.S. and Europe, against Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, against communist tyranny in Tiananmen Square and Eastern Europe. Protest was the natural continuation of politics by other means.

Then came the End of History, summed up by Francis Fukuyama's influential 1989 essay... The two decades beginning in 1991 witnessed the greatest rise in living standards that the world has ever known. Credit was easy, complacency and apathy were rife, and street protests looked like pointless emotional sideshows--obsolete, quaint, the equivalent of calvary to mid-20th-century war. The rare large demonstrations in the rich world seemed ineffectual and irrelevant. (See the Battle of Seattle, 1999.)

It is stunning that I had never thought of this before, because in my history classes and even in simple living in this world, I have often thought of the protests of old as exactly that, as relics of eras gone past, a people, a group, a generation more connected, more concerned, and more committed to bringing change and making a difference than anything my generation could or would ever see. It seemed complacency had replaced this spirit of fighting, caring, standing up against The Man.

And then 2011 came out of nowhere. Spontaneous protests, beginning with a fruit vendor in Tunisia last December, and his death on January 4, 2011, snowballed around the globe, North Africa and the Middle East, in Europe, Asia, North America. But, historically, it was right on time:

In short, 2011 was unlike any year since 1989--but more extraordinary, more global, more democratic, since in '89 the regime disintegrations were all the result of a single disintegration at headquarters, one big switch pulled in Moscow that cut off the power throughout the system. So 2011 was unlike any year since 1968--but more consequential because more protestors have more skin in the game. Their protests weren't part of a counterculture pageant, as in '68, and rapidly morphed into full-fledged rebellions, bringing down regimes and immediately changing the course of history. It was, in other words, unlike anything in any of our lifetimes, probably unlike any year since 1848, when one street protest in Paris blossomed into a three-day revolution that turned a monarchy into a republican democracy and then--within weeks, thanks in part to new technologies (telegraphy, railroads, rotary printing presses)--inspired an unstoppable cascade of protest and insurrection in Munich, Berlin, Vienna, Milan, Venice, and dozens of other places across Europe, as well as huge peaceful demonstrations of democratic solidarity in New York that marched down Broadway and occupied a public park a few blocks north of Wall Street. How perfect that the German word Zeitgeist was transplanted into English in the unprecedented, uncanny year of insurrection.

That's an extraordinary paragraph to consider. How 2011 is unlike anything we've seen in many, many dozens of years--arguably since 1848! Also, I finally had to look up the root of the word zeitgeist, as too many intellectuals and writers have been brandishing that thing around, and it means, "the spirit of the day." In fact, 2011 has a very distinct spirit, changing the course of what all the years to follow might hold.

This year has made many commentators reconsider things they thought were political, social, academic truths. I took several courses during my undergraduate years on global politics, and especially on Southeast Asia (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh), and East Asia (China, Japan, Koreas, etc.), and what we spent a lot of time discussing was the misconceptions our own countrymen had been laboring under as they sparked the last decade of war, and many of the current skirmishes we continue to manage. A lot of those class sessions might involve some serious reconsideration after all, and eating of our words, as we see the demands and freedoms protestors are asking for now, in this moment, themselves. No matter your opinions on the wars we have been fighting, it has been pretty stunning to see the events unfolding, lead by those citizens of the nations, who may want the same things as us, after all. Where these revolutions head now, only time will tell. But it has been an incredible year.

This year has made many commentators reconsider things they thought were political, social, academic truths. I took several courses during my undergraduate years on global politics, and especially on Southeast Asia (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh), and East Asia (China, Japan, Koreas, etc.), and what we spent a lot of time discussing was the misconceptions our own countrymen had been laboring under as they sparked the last decade of war, and many of the current skirmishes we continue to manage. A lot of those class sessions might involve some serious reconsideration after all, and eating of our words, as we see the demands and freedoms protestors are asking for now, in this moment, themselves. No matter your opinions on the wars we have been fighting, it has been pretty stunning to see the events unfolding, lead by those citizens of the nations, who may want the same things as us, after all. Where these revolutions head now, only time will tell. But it has been an incredible year.

I think what Andersen has done best, with both of these pieces in separate magazines, has been to show how we are simultaneously experiencing everything the same and nothing the same. And for some reason, this contradiction makes perfect sense. Reading these two articles almost back-to-back (absolutely unintentionally), one reads as a cautionary tale of a western culture gone a bit stale, the other as a means by which to rediscover ourselves, our values, and what is important in this life. And this year has been the perfect one in which to discover both these truths about ourselves, and to seek to bring them together harmoniously, using them for renewal, reaction, redemption, reward in years to come.